Does Policy Coherence Matter?

By Pamodi Hewawaravita and Karin Fernando

Agriculture is at the heart of rural economies; sustaining livelihoods over generations and sustaining food production systems and the health and wellbeing of people all over the world. However, farmers, especially small-scale farmers, are usually the first line of defense to fall prey to the combined effects of the economic crisis and climate change, and Sri Lanka has not been immune to this phenomenon. Today, as we face limited growth and reduced natural capital, it is vital to balance multiple objectives of resilient livelihoods, food security, economic development, and environmental sustainability in more effective and efficient ways. Policy coherence can be an enabler for achieving these multiple, often conflicting goals.

What is policy coherence?

Policy coherence can be defined as a process of policy making that systematically considers the pursuit of multiple policy goals or objectives in a coordinated way, minimising trade-offs, and maximising synergies (Nilsson, 2021). This means that by interlinking policy design and implementation, it should be possible to recognise and address negative outcomes (trade-offs) and capitalize on policies that complement and build on each other (synergies). Policies that are coherent by intention are also expected to address inequality. Therefore, policy coherence is an important part of achieving sustainable development given the need to balance between economic, social, and environmental dimensions and the need to address equitable development.

Sustainable agriculture in Sri Lanka

Applying policy coherence to the agriculture sector means that for better outcomes, it would be necessary to achieve economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability. To highlight an example, a coherent policy could make food that is less expensive available without polluting the water source while an incoherent one could do the opposite.

Although successive Sri Lankan governments have tried their hands at numerous policy responses to address the inequalities and vulnerabilities within the agriculture communities in the country, they continue to live in poverty, with low levels of productivity. Thus, the effectiveness of these policy processes, and the methods in which they were implemented, requires scrutiny.

The fertiliser ban and policy coherence

Sri Lanka is still struggling to recover from the negative impacts of one of the most controversial agriculture policies in its history – the ban on chemical fertilizer. Its overnight implementation – in April 2021 and its subsequent reversal – November 2021, left the farming community reeling.

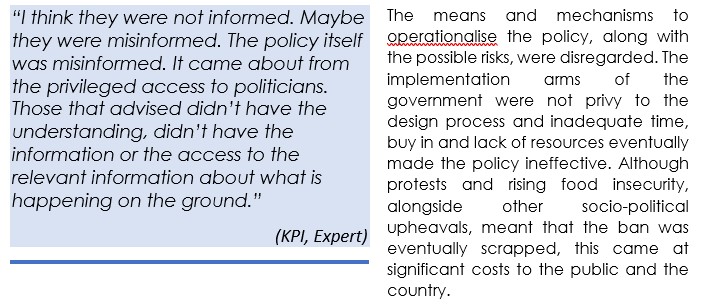

The fertiliser ban is an interesting case study on the policy process in Sri Lanka. Although by design it supported the concept of organic farming and healthier food, the overnight implementation was a result of the economic crisis and a lack of forex to purchase chemical fertiliser. In interviews CEPA conducted with experts, it became apparent that stakeholder consultation was not carried out effectively regarding this particular policy.

Social, economic, and political outcomes

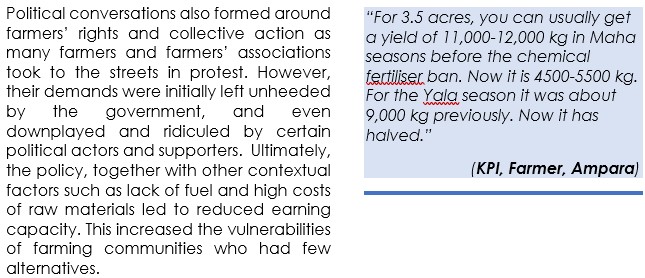

The ban had negative social, economic, and political outcomes. Farmers lament that unprecedented U-turns and incoherent agriculture policies such as the sudden ban on chemical fertiliser came at the cost of their income and their economic standing.

Environmental outcomes

While expected environmental outcomes of the ban were positive to note, the haphazard, ad hoc, and sometimes termed ‘cruel’ implementation of the ban meant that farmers lost their trust in the potential to use organic fertilizer. It also cast doubt on the policy making process as it showed how science and expert knowledge were made redundant in the face of political gain.

Since organic farming builds resilience over time, had it been introduced gradually or had the recommended 70 (inorganic):30 (organic) ratio for applying fertilizer been enforced, with better guidance and support to access fertilizer, the policy change may have yielded better results. However, since farmers were not involved in the policy process, they were not able to voice their opinions or concerns but had to face the consequences.

Conclusion

As the fertiliser ban in Sri Lanka shows, policy coherence to achieve economic growth, environmental sustainability, and social inclusion requires thorough planning, good implementation, a suitable transition period, while being inclusive at all stages of the policy process. This is not something that can be achieved without strong commitment and collaboration with a range of stakeholders. It also points to the need for a long-term time horizon that allows for the idea to take root with checks and balances to adapt.

The fertilizer ban and indeed many other agriculture policies show the consequences of vested interests, that lead to policy incoherence and the eventual fall out of policy outcomes.

In addition, while policy designs may be coherent and address multiple policy objectives, if enough emphasis is not given to implementation, the outcomes are not achieved and can also lead to inequitable outcomes. Even if they are unintended, they can exacerbate existing inequalities or create new inequalities.

This blog is based on a research study on policy coherence done in collaboration with the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI). Click here for the summary report on policy coherence workshop held in Sri Lanka.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of CEPA