Communication, Collaboration, and Innovation: The Value of Community-Based Approaches to COVID-19 in Sri Lanka

Description

Published June 2022, revised January 2023

Fiona Carter-Tod

Abstract

Despite the previous success of Sri Lanka’s universal health care (UHC) system, the country has begun to face novel challenges such as non-communicable diseases (NCDs), an aging population, and, most pressingly, the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous pandemic and disaster response and recovery worldwide have centered local community approaches as a crucial element in effective solutions. Thus, in many countries, the importance of community-level interventions within their pandemic response has been recognized and emphasized. However, there is a gap in the literature surrounding the role of community organizations in Sri Lanka’s pandemic response. This paper aims to investigate the role of community organizations and community-based responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka through a literature review and interviews with public health professionals. In addition, within the context of outlining their role, this paper intends to discuss the potential translational nature of the involvement of community organizations as it pertains to other pressing issues within the Sri Lankan public health system.

Introduction

Community-based approaches are becoming of increasing importance to public health. The modern view of public health extends beyond physical services and wholistically encapsulates health education, health literacy, preventative medicine, and more. Thus, many scholars are looking into multisectoral approaches to public health issues. Global leaders in public health have repeatedly emphasized the importance of community-based approaches to equitable and effective public health (Saxon and Ford 2021). For the function of this study, community-based approaches will serve as an umbrella term for modalities and strategies implemented by community groups, organizations, and individuals that help to identify and address collective problems and strengthen collective goals (Saxon and Ford 2021). Community-based approaches to public health, especially those implemented by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and community organizations, are valuable because they involve collaboration, empowerment, and a prolonged presence (Saxon and Ford 2021). Given these abilities, it has been indicated that the inclusion of community-based interventions in public health efforts facilitates sustainable relationships, the distribution of power, the identification and changing of ineffective policies, support for productive dialogue, increased trust, and combatting health disparities through information dissemination and resource access (Saxon and Ford 2021).

This paper intends to engage in the conversation of community-based approaches to the most recent pressing global health issue, the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature indicates that countries turned to community-based approaches during their pandemic response. In this vein, the intention of this study is to investigate the role that community-based approaches and community organizations played in the pandemic response in Sri Lanka. In addition, the previously successful Sri Lankan public health system has begun to falter in the face of rising incidences of NCDs. Due to this increase, this paper aims to outline the current perspectives on applying community-based interventions utilized during the pandemic to other pressing public health issues in Sri Lanka. Finally, some challenges to utilizing community-based approaches in Sri Lanka are addressed.

Methods

Overall, this study is based on qualitative ethnographic inquiry supported by a detailed literature review. The purpose of the literature review is to provide background by; a) outlining the structure and success of the Sri Lankan public health system and its handling of COVID-19, b) exploring the value of community organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic in a global context, and c) engaging with existing literature on the role of community organizations in Sri Lanka. The literature review is a non-systematic review that was conducted using primarily Google Scholar. Each search was executed with a set of words. The sets utilized are as follows; (a) community organizations, COVID-19 (b) community organizations, pandemic (c) community organizations, COVID-19, Sri Lanka (d) Sri Lanka, the public health system. The articles of most relevance were chosen and included. The review does not intend to be wholly comprehensive but rather a thorough synopsis aimed at contextualizing the topic studied here.

The primary intention of the interviews was to gather the current professional perspectives on the impact and handling of the COVID-19 pandemic from both those that work within the public health sector as well as community organizations that potentially assisted with public health efforts. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format and lasted between 20 and 50 minutes. The questions asked were adapted based on the categorization of each public health professional but generally fell under the schema of three broader inquires:

- How has the pandemic affected the Sri Lankan public health system?

- What role, if any, did community organizations play in the pandemic response?

- If community organizations did contribute to the pandemic response, is there a potential for these contributions to be helpful in the face of other pressing public health issues?

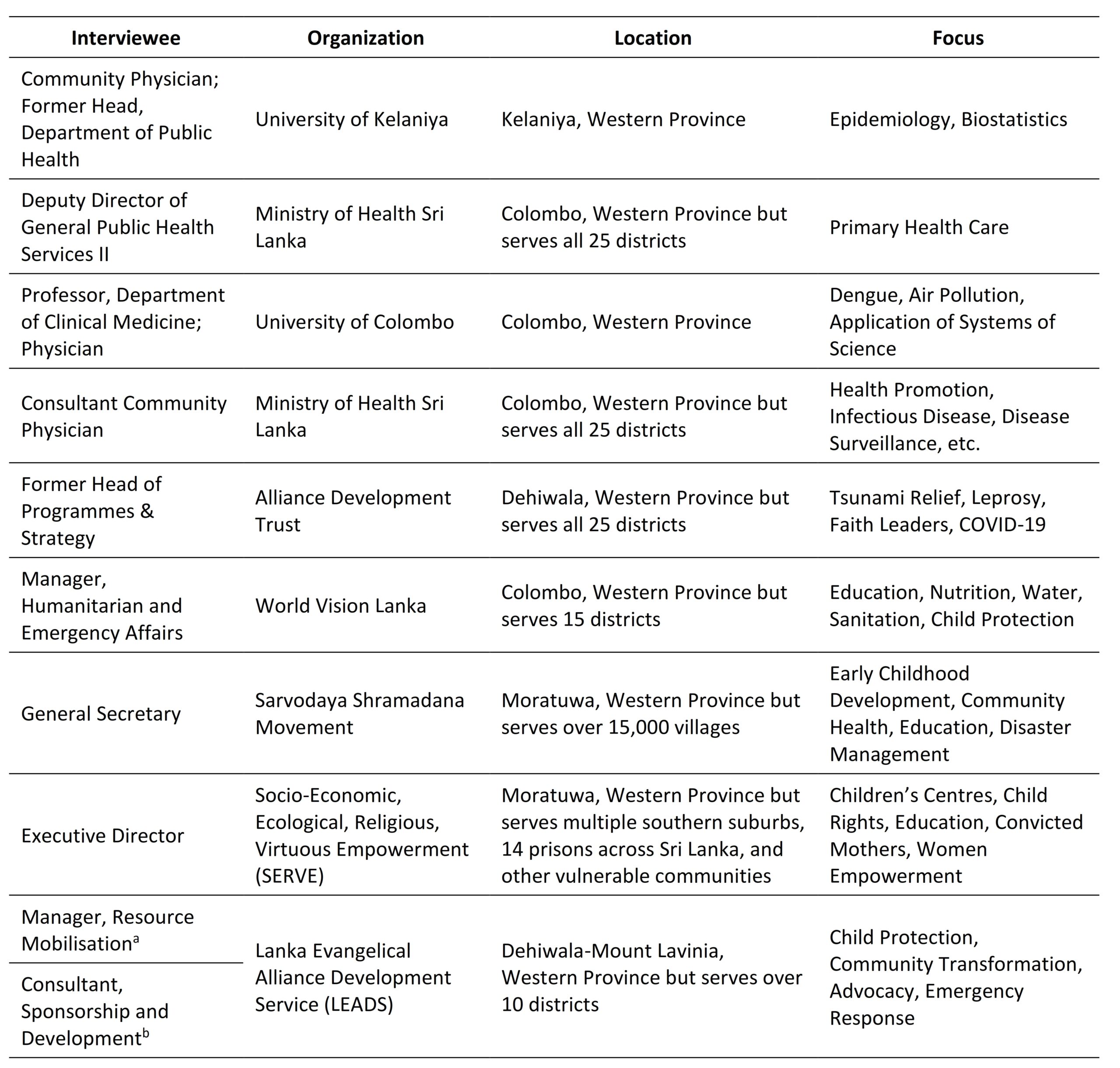

Individuals were chosen based on their connection to, knowledge of, and experience with the Sri Lankan public health system. The selection process was primarily done via two different routes. Firstly, in the process of investigating relevant literature, authors of existing work investigating the role of community-based approaches in Sri Lanka and South Asia were contacted. Secondly, through scanning the NGO registry as well as via a general web search, leaders of various Sri Lankan community organizations were also contacted. After email and phone communications, ten professionals were interviewed in total. Each public health professional generally fell into one of the following categories: a) physician/academic, b) community organization affiliate, and c) governmental health policy employee (Table 1). The interviews were primarily conducted via video call with the exception of a few that were conducted in the office of the respective professional. In line with the comfort and consent of each participant, interviews were recorded either audibly or both audibly and visually. The interviews were manually transcribed and analyzed using thematic content analysis. Each interview was examined for information relevant to public health, NGOs, community, and COVID-19. As a result, excerpts were pulled and categorized. These categories were then reread as a collective and patterns were observed and noted. The extracted information is presented in a narrative analysis format as it relates to the topic at hand.

Table 1. Description of Interviewees Positions, Associations, and Focus Areas

a Individual was interviewed at the same time as another representative from the same organization

b Individual was interviewed at the same time as another representative from the same organization

Literature Review

Sri Lanka’s healthcare system comprises a tax-funded public system supplemented by a fee-for-service private sector (Kumar 2019). The public health system had its beginnings in the 1930s when public hospitals charged user fees only to those able to pay (Rosenburg 2018). When Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, health facilities were required to accept any patient who sought admission, and by 1951, all user fees were abolished (Smith 2018). Since then, the government has provided some form of universal health care services (Smith 2018, Rosenburg 2018). The infrastructure of the public health system can be most easily understood within the context of its two modalities: its preventative and care efforts. Most well-known is the preventative service delivery that consists of decentralized provincial departments of health through 26 health regions containing health units (Kumar 2019). The health units were established in Sri Lanka in 1926 and were responsible for disease prevention, health education, and maternal and child welfare (Rosenburg 2018). Today the health unit system is a network of over 340 Medical Officers of Health (MOH) supported by assistant medical officers of health, public health nurses, public health midwives, and public health inspectors (Kumar 2019 and Rosenburg 2018). On the other hand, the care sector consists of 1105 facilities, spanning primary, secondary, and tertiary levels (Kumar 2019). In addition, in October 2018, the Ministry of Health adopted a new policy that centered a “shared care cluster” model (Kumar 2019 and Perera 2019). This model, still in its implementation phase, moves away from the previous practice of users accessing their preferred public facility and redirects to a referral-based model that consists of units of a public-sector specialist care center and its surrounding primary-care facilities (Perera 2019).

Having outlined the structure of the public health system, it is important to note its success. The remarkability of this system can be attributed to extensive geographic spread at relatively low levels of spending (< 2% of GDP), walk-in services with no charges, and impressive reporting on health indicators (Kumar 2019). The most notable of these indicators are the system’s advances in maternal health, child health, and infectious disease containment. In 2018, the country had a maternal mortality rate of 33.8 per 100,000 births and an infant mortality rate of 9 per 1,000 live births, both of which are less than half the respective Sustainable Development Goal targets for 2030 (Smith 2018). In addition, the maternal mortality rate is the lowest in the South Asian region (Kumar 2019). Regarding the containment of infectious diseases, the country has eliminated malaria, measles, polio, rubella, lymphatic filariasis, neonatal tetanus, and mother-to-child transmission of HIV (Perera 2020, Adikari 2020, Kumar 2019). Despite these achievements of the Sri Lankan public health system, there has been a shift in the public health landscape. The issues of maternal health, child health, and infectious disease continue to be successfully addressed, but issues regarding non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and an aging population have risen (Smith 2018). Addressing NCDs requires the repeated utilization of preventative and curative services (Smith 2018). This need for repeated use has proven to challenge Sri Lankan care services. As the current system has been described as less organized and insufficient in its provision of nonessential drugs, conclusions regarding interventions by community organizations during the pandemic will be valuable in the face of rising incidences of NCDs (Smith 2018 and Kumar 2019). Although the newly adopted “shared care cluster” model attempts to address this issue, it is debated whether it goes about it correctly (Kumar 2019).

In addition to a struggling care sector, most recently Sri Lanka, like the rest of the world, has had to face the most novel of challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic. On January 27, 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Sri Lanka, and within 2 months, all international airports were closed, and an island-wide curfew was imposed (Weerasinghe 2020). Despite managing the first wave, the Sri Lankan public health system was challenged by the novelty of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequently suffered at the hands of the second and third waves. The second wave began in September of 2020 and spread to the whole island by January 2021 (Rajapaksa, De Silva, Abeykoon 2022). The third wave began in April 2021, around the time of the Sinhala and Tamil New Year, and proved to be the most devastating (Rajapaksa, De Silva, Abeykoon 2022). When tackling the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic the public health response involved interventions such as detection, cluster-based containment, reduction of social gathering and mobility of the population, isolation, treatment, and staggered relaxation of control measures (Weerasinghe 2020). The MOH system we hope that there will be a continued engagement on this process and proved useful and focused on early case identification and management, isolation of cases, contact tracing, quarantine of suspected persons, surveillance, risk communication, and creating a wide level of awareness among the public on personal hygiene measures to “stay safe” (Rajapakse, De Silva, Abeykoon 2022).

Whereas much of the literature surrounding the Sri Lankan pandemic response focuses on the robust preventative health system, there is a lack of mention of non-governmental pandemic support. Outside of Sri Lanka, research on crisis response and recovery has often indicated, such as in the case of AIDS and SARS, the success and sustainability of responses that emerge from a community level (Routte et al. 2022 and Michener et al. 2020). Community organizations can be utilized to support public health interventions, ensure participation, promote accountability toward at-risk populations, and focus on behaviors and actions (Rachmawati et al. 2022). The World Development Report has repeatedly called for NGOs to have an increased significance in their roles in improving service quality and filling existing gaps in healthcare services (Widmer et al. 2011). Within the context of the COVID-19 crisis, many countries emphasized the importance of collaboration with community organizations. For example, in Indonesia, it was found that faith-based organizations (FBOs), some of the forerunners of NGOs and community-based work, played a pivotal role during the pandemic (Rachmawati et al. 2022). More specifically, it was found Islamic FBOs were vital in reaching the grassroots, supporting primary and secondary prevention programs, and minimizing the impact of COVID-19 (Rachmawati, et al. 2022). In the Zhejiang Province of China, Cheng et al. establish that the interaction between community-based organizations and their local governments was one of the key determinants in the coproduction of effective COVID-19 containment strategies (Cheng, et al. 2020). In the Midwest of the United States, effective COVID-19 case management, outreach, programming, and advocacy effectively emerged from the organizational embeddedness and flexibility of refugee-led community organizations proving them to be crucial in crisis response (Routte et al. 2022). In Amsterdam, Netherlands community-based youth organization initiatives built on well-developed partnerships with the city government and maximized community engagement with government-funded relief efforts (Roels et al. 2022). In Oman, the Ministry of Health initiated community participation as one of the key components in their pandemic response (Al Siyabi et al. 2021). Three community-based approaches were implemented, the first of which was utilizing community organizations within cities and villages to facilitate networking, act as a platform for engagement, review health information, and provide updates (Al Siyabi et al. 2021).

As other countries have emphasized the value of community organizations during the pandemic, this conversation can extend to Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka, NGOs can be broadly defined as any “voluntary organization” or “organizations receiving foreign funding who engage in donor-funded projects in return” (Priyadarshanie 2014). Outside of the pandemic, literature addressing community organizations in Sri Lanka mainly focuses on post-war development following 2009, post-tsunami relief following 2004, and LGBTQ+ support (Akurugoda 2014). Many of these NGOs address problems involving human rights violations, issues with decentralization, and local- and community-led development (Akurugoda 2014). Narrowing from all NGOs to literature on NGOs with general health interventions, there are discussions of community organizations aiding in public health issues. Specifically, it is discussed that NGOs played a significant role in Sri Lankan nutrition interventions, despite the efforts often being government-originated and government-sponsored (Karunanayake 1982). Saxon and Ford also indicate that community organizing can improve health among underserved populations in Sri Lanka by using community organizing to develop local engagement and participation (Saxon and Ford 2021). The effect of the support of these organizations is already proven, and much like in other countries, in the face of COVID-19, they turned to use their resources for the pandemic crisis response. The following interviews will qualitatively explore their role during the pandemic response and the implications this role has for community-based interventions in Sri Lankan public health moving forward.

Results

Despite current literature outlining the involvement of community organizations in Sri Lanka beyond the context of the pandemic, the overall impact, perception, and future potential remains to be fully explored and outlined. Therefore, this section draws a multisectoral understanding from the in-depth interviews conducted with public health professionals on how these organizations performed during the pandemic response. The professionals spanned a wide range of involvement in public health; many occupy multiple positions but have been grouped (physicians/academics, community organization affiliates, governmental health policy employees) for the purpose of succinct explanation. The individuals included were representatives of one large Sri Lankan community-based development organization, one Sri Lankan faith-based NGO, two small Sri Lankan NGOs, and one large international humanitarian aid organization. Through these interviews, it was found that the most common forms of practical support provided by community organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic included fundraising to provide dry rations packs, the collection and distribution of safety equipment (PPE, hand sanitizer, soap, etc.), and the development and collection of educational materials for children participating in online learning. Beyond the provision of resources, the main thematic take aways repeatedly mentioned by interviewees included the unique ability of community organizations to communicate with communities, collaborate with government efforts, and develop innovative approaches and solutions.

Practical Support

The large international humanitarian aid organization, World Vision Lanka, focused on both assisting communities and supporting health facilities as two separate ventures. Through providing income assistance, pandemic education, psychosocial support, dry rations to daily waged laborers, and online educational support they assisted communities. In addition, they supported health facilities through the provision of equipment, PPE kits, hygiene kits, and more. The two small Sri Lankan NGOs, LEADS and SERVE, focused more on specific populations. LEADS distributed dry ration packs, organized vaccine drives, and was heavily involved in supporting children in Child Development Centers (CDCs) through child-specific ration pack and recreational items. SERVE provided support for basic needs for children under five living with their mothers in the remanded and convicted section at Welika and Kalutara Prisons. The organization provided dry rations to all the children in their weekly programs and women in their Women’s Groups. A large Sri Lankan community-based development organization, Sarvodaya, equipped villages to be “pandemic ready villages.” This effort included community monitoring of public health compliance, community empowerment, and launching programs and initiatives to address the long-term impacts of COVID-19 on economic and social factors. In addition, they dispersed essential supplies and relief packages, screened awareness messages, and engaged in regular discussions of national and district-level developments. The religious-based NGO, the Alliance Development Trust (ADT), translated a strategy from their previous leprosy program to the COVID-19 response and brought together religious leaders from every district to collaborate and disseminate important messages regarding pandemic safety, policies, and practices. (Wijesinghe et al. 2022).

Beyond the provision of resources, interviewees repeatedly touched on the perceived benefit of community organizations beyond just supplementing practical support. These main touchpoints included the unique ability of community organizations to communicate with communities, collaborate with government efforts, and develop innovative approaches and solutions.

Communication with Communities

Public health professionals repeatedly spoke of the value of communication facilitated by community organizations. The value of a community-based approach is rooted in the presence of trust, thusly these existing bridges were utilized to effectively communicate essential information regarding pandemic safety. Two community organization affiliates spoke of the strength of collaboration both amongst community organizations and with their partners, such as stakeholders, government officials, religious leaders, and community members. In addition, two other public health professionals viewed this ability as easily applicable to other emerging public health issues.

Collaboration with Government Efforts

Six out of the ten public health professionals interviewed mentioned the strength and success of the public health system. This evidence is consistent with the existing literature. Specifically, it was repeatedly emphasized that the strength of the existing preventative infrastructure allowed for the effective handling of the first wave of the pandemic. Also mentioned was the benefit of the extensive breadth of services provided by the health system. They viewed that the diversity of services and the multifunctional nature of the system allowed for a greater capacity to adapt in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, government efforts still present opportunities for NGOs to fill in gaps. One interviewee spoke about the potential for community organizations to get vaccination numbers up by directly supporting the government vaccination program. Interviewees explained that community organizations are effective when aiding in government responses rather than exclusively organizing and implementing programs independently. This finding highlights the need to extend and build from platforms already in place.

Innovative Approaches and Solutions

When asked about the emerging challenges to health in Sri Lanka, such as NCDs, half of the public health professionals spoke of a need for innovative solutions. Interviewees from community organizations spoke of approaches to the pandemic that exemplified the innovative thinking of NGOs. Among the unique approaches utilized by the organizations interviewed were the use of computerized community monitoring, the development of online learning technology, the writing of a children’s book explaining COVID-19, the organization of committee meetings of NGOs in the same action areas, and the mobilization of trusted religious leaders. These ideas, although specific to the pandemic, show that organizations plugged into the needs and ideas of local communities possess a capacity for creative thinking and implementation. This skill is vital and beneficial to utilize in the face of other health issues challenging Sri Lanka’s current system.

Discussion

Though the impact of community organizations on pandemic control has been established worldwide, it has not been wholly recognized in Sri Lanka. It was found that leaders from NGOs of various sizes outlined multiple methods of intervention in response to the pandemic including fundraising, the provision of kits, and supporting online learning. The primary perceived value of community organizations in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic is rooted in their potential for improved communication, collaboration, and innovation. Despite potential challenges, these three themes potentially provide an architecture for more effectively combatting other public health concerns, specifically those that involve long-term interventions such as NCDs and the negative health effects of the economic crisis. These conclusions parallel other work currently being done in this area. For example, the President of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement has been quoted by The Daily Financial Times as he concluded that “handling a pandemic of this nature cannot be accomplished by the government alone. The community-based organisations and community leaders should also play an important role in supplementing the work of the government” (Ariyaratne 2021 and Wijewardena 2022). Although not directly addressed, discussions of implementation, accountability, and feasibility modalities are important next steps to the inclusion of community-based approaches to public health issues. Going forward as Sri Lanka has begun to face other crises that affect public health, such as the current economic crisis, it will be important and valuable to continue this investigation into the unique position and powerful role of community organizations.

Study Limitations

There are a few limitations to the preceding conclusions. The first of which is the classification of Sri Lanka’s healthcare system. Throughout this paper, the system is referred to as being “universal.” It is important to note that despite Sri Lanka’s healthcare system’s official classification being “universal” there are claims that this is becoming increasingly untrue. Chapman and Dharmaratne argue that because Sri Lanka is no longer providing good healthcare at a low cost due to the limitations of insufficient governmental health expenditure, an over-reliance on an inequitable private sector, and a failure to satisfactorily respond to the emerging epidemic of NCDs, the system no longer qualifies as a universal healthcare system (Chapman and Dharmaratne 2019). This is significant as it only further emphasizes the public health system’s increasing need for support. For the function of this study, Sri Lanka’s healthcare system was referred to as universal, but it is important to recognize that the growing and changing perspectives on the current system provide valuable contextualization to changing health and economic landscape.

Another limitation is the lack of discussion of the potential translational nature of NGOs and community organizations that work successfully with marginalized populations such as sex workers and the LGBTQ+ community. NGOs involved with the LGBTQ+ community, such as the well-known Equal Ground, have provided a wide range of services and resources that include safe spaces, screening queer films, providing access to queer literature, advocating for rights, and more (Arteta Gonzalez 2019). In addition, NGOs that support sex workers have been integral in the dissemination of information about HIV/AIDS and collaboration on HIV/AIDS prevention strategies with governmental and non-governmental bodies (Arteta Gonzalez 2019). Given the presence of these organizations in topics of public health, it could be presented that they are positioned to provide better translational strategies for addressing rising Sri Lankan public health issues than those implemented in response to COVID-19. In response, this paper does not intend to imply that strategies implemented by NGOs and community organizations during COVID-19 are exclusively useful in addressing rising public health issues but rather generally emphasizes the value of community-based approaches to these issues. Thusly, further research into translational strategies from LGBTQ+ and sex worker-focused organizations would be an effective addition to the conclusions of this paper.

Finally, the limitation of the role of governmental control and community distrust of NGOs is important to note. The role of NGOs is both political and controversial. As previously stated, post-war and post-tsunami community organizations and NGOs became significantly involved in development interventions of reconstruction, relief, and rehabilitation (Akurugoda 2014). During these times, aid mismanagement became an increasing problem as NGO collaboration and handling large amounts of foreign aid were relatively new to some local governments (Akurugoda 2014). In March 1990, an NGO commission was established by the then Executive in order to investigate aid mismanagement as well as a lack of monitoring among other things (Akurugoda 2014). The commission effectively discredited NGOs and associated them with negativity and (Akurugoda 2014). It is argued this association was purposeful in an effort to allow for government control of NGO activities and to avoid NGOs becoming involved in human rights protection (Akurugoda 2014). In addition to this controversy, Sinhala nationalist parties and groups tend to view NGOs as imperial agents and threats to the sovereignty of the country (Akurugoda 2014). There is literature that supports that although distrust exists, NGOs which directly connect with the local Sri Lankan government are more successful, focused, influential, and can play a positive role in empowering local government and communities in addressing development needs (Akurugoda 2014). Although this paper does not directly engage with the controversy and political nature of NGOs, it intends to contribute to the discussion of the unique position and impact of NGOs.

Acknowledgments

The kindness and insight given by all the public health professionals interviewed were greatly appreciated. In addition, gratitude must be expressed for the support and guidance of Karin Fernando, Minuri Perera, Chandima Arambepola, Saranie Wijesinghe, and many more associated with the Centre for Poverty Analysis.

References

Adikari, Pamila Sadeeka, et al. “Role of MOH as a grassroots public health manager in preparedness and response for COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka.” AIMS Public Health 7.3 (2020): 606.

Akurugoda, Indi Ruwangi. “The politics of local government and development in Sri Lanka: An analysis of the contribution of non-governmental organisations (NGOs).” Diss. University of Waikato, 2014.

Al Siyabi, Huda, et al. “Community participation approaches for effective national covid-19 pandemic preparedness and response: an experience from Oman.” Frontiers in public health (2021): 1044.

Ariyaratne, Vinya S. “The importance of community engagement in combating COVID-19.” COVID 19: Impact, Mitigation, Opportunities and Building Resilience: Perspectives of global relevance based on research, experience and successes in combating COVID-19 in Sri Lanka, National Science Foundation Vol. 1. (2021): 69-77.

Arteta Gonzalez, Joshua. “Repainting the Rainbow: A Postcolonial Analysis on the Politics of the LGBTQ Movement in Colombo, Sri Lanka.” (2019).

Ellawala, Themal. “Legitimating violences: The ‘gay rights’ NGO and the disciplining of the Sri Lankan queer figure.” Journal of South Asian Development 14.1 (2019): 83-107.

Chapman, Audrey R., and Samath D. Dharmaratne. “Sri Lanka and the possibilities of achieving universal health coverage in a poor country.” Global Public Health 14.2 (2019): 271-283.

Cheng, Yuan, et al. “Coproducing responses to COVID‐19 with community‐based organizations: lessons from Zhejiang Province, China.” Public Administration Review 80.5 (2020): 866-873.

Karunanayake, H. C. “Community-level nutrition interventions in Sri Lanka: A case study.” Food and Nutrition Bulletin 4.1 (1982): 1-10.

Kumar, Ramya. “Public–private partnerships for universal health coverage? The future of “free health” in Sri Lanka.” Globalization and Health 15.1 (2019): 1-10.

Michener, Lloyd, et al. “Peer reviewed: engaging with communities—lessons (re) learned from COVID-19.” Preventing chronic disease 17 (2020).

Perera, B. J. C. “Elimination of several infectious diseases from Sri Lanka: A tribute to the parents of our children and to our immunisation programme.” Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health 49.4 (2020).

Perera, Susie, et al. “Accelerating reforms of primary health care towards universal health coverage in Sri Lanka.” WHO South-East Asia journal of public health 8.1 (2019): 21-25.

Priyadarshanie, P. K. D. “The effectiveness of the communication in community development projects implemented by the Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in Sri Lanka.” (2014).

Rachmawati, Emma, et al. “The roles of Islamic Faith-Based Organizations on countermeasures against the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia.” Heliyon 8.2 (2022): e08928.

Rajapaksa, Lalini C., Padmal De Silva, and Palitha Abeykoon. “COVID-19 health system response monitor: Sri Lanka.” (2022).

Roels, Nastasja Ilonka, et al. “Confident futures: Community-based organizations as first responders and agents of change in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic.” Social Science & Medicine 294 (2022): 114639.

Rosenberg, Julie, et al. “Positive Outlier: Sri Lanka’s Health Outcomes over Time.” Harvard Business Publishing, (2018).

Routte, Irene, et al. “Refugee-Led Organizations’ Crisis Response During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees/Refuge: Revue canadienne sur les réfugiés 38.1 (2022): 62-77.

Saxon, Andrew, and Jessie V. Ford. ““Now, I am Empowered. Now, I am a Woman With Spirit”: Evaluating CARE’s Public Health Work Through a Community-Organizing Framework in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.” International Quarterly of Community Health Education 41.3 (2021): 241-258.

Smith, Owen. “Sri Lanka: achieving pro-poor universal health coverage without health financing reforms.” World Bank, (2018).

Weerasinghe, M. C. “Co-existing with COVID-19: Engaging the community to strengthen the public health response in Sri Lanka.” (2020).

Widmer, Mariana, et al. “The role of faith-based organizations in maternal and newborn health care in Africa.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 114.3 (2011): 218-222.

Wijesinghe, Millawage Supun Dilara, et al. “Role of Religious Leaders in COVID-19 Prevention: A Community-Level Prevention Model in Sri Lanka.” Journal of religion and health 61.1 (2022): 687-702.

Wijewardena, W. A. “COVID-19 pandemic: A brief to Sri Lanka’s authorities by the scientific community.” The Daily FT, (2022). https://www.ft.lk/columns/COVID-19-pandemic-A-brief-to-Sri-Lanka-s-authorities-by-the-scientific-community/4-728945